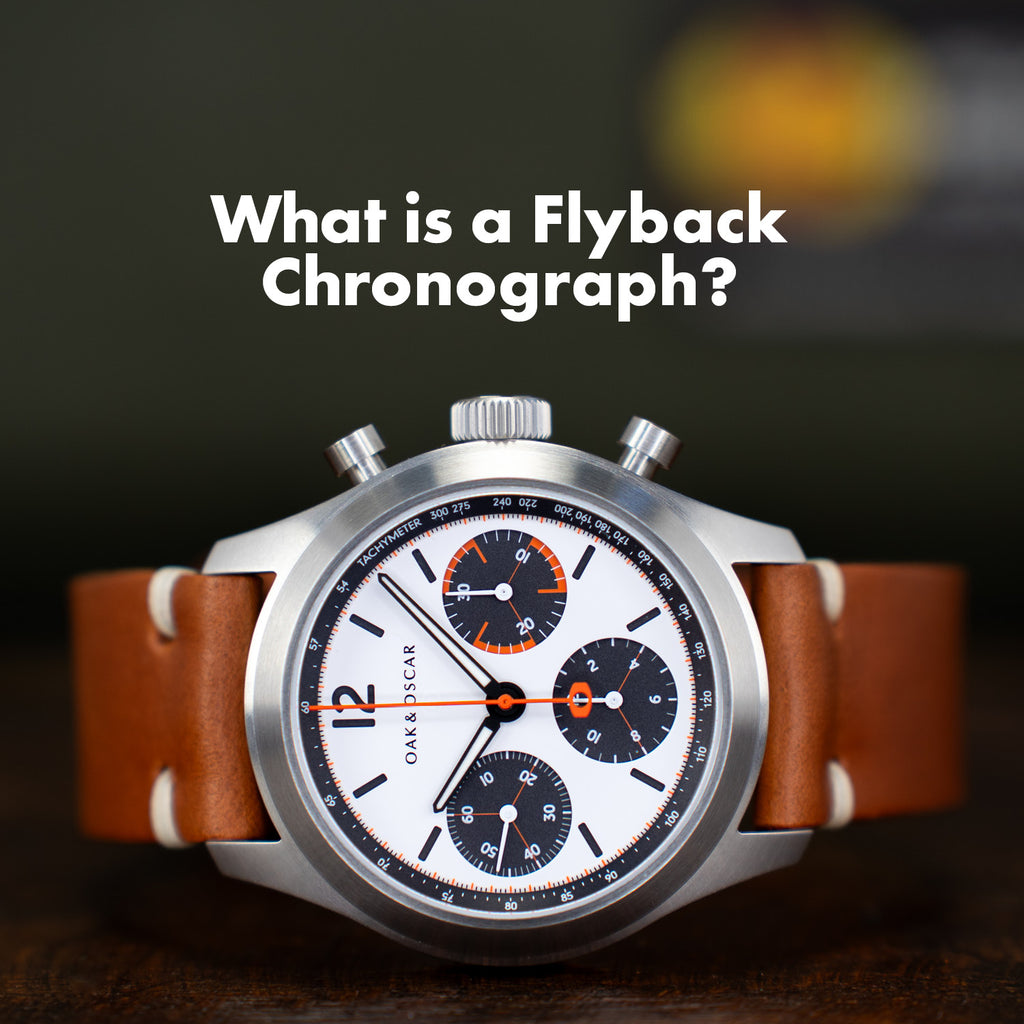

From the Bench: What is a Flyback Chronograph?

A cool feature of some chronographs is that they have a “flyback” design, but what exactly does that mean? On a traditional chronograph, you can start and stop the timing, but you can reset only when it’s stopped. On a flyback, you’re able to reset at any time.

Below is a diagram of the flyback movement in the A. Lange & Söhne Datograph.

This is important if you’re timing a race with multiple laps. On a traditional chronograph, you’d need to stop at the end of the lap, and then quickly reset and restart the chronograph—losing a precious half-second or more. In many races, that can be a huge error. With a flyback, at the end of the lap you can simply reset as the chronograph runs, allowing you to track lap times precisely.

To be more precise, a flyback is a chronograph that allows you to reset it while at any time, without breaking everything.

That italic portion is important. Chronograph reset actions are incredibly violent (in watchmaking terms, at least), and chronograph components are fragile. To avoid breaking things, a flyback also has to get all of those delicate components out of the way before it zeros out the counter wheels.

While a chronograph is running, the clutch takes power from the movement and uses it to drive the chronograph wheel—the seconds counter—which drives everything else indirectly. The clutch typically takes power off of the 4th wheel, which is a relatively low-torque part of the movement.

Low torque requires delicate components, so the clutch and chronograph wheels typically have small, fragile triangular teeth. Triangular teeth aren’t perfectly optimal for low-friction power transmission, but they’re amazing for instantaneous engagement. Most chronographs are “horizontally clutched,” which means that two wheels on the same plane will mesh together to drive the mechanism. Triangular teeth naturally slide together to self-mesh, while regular involute teeth might accidentally jam on each other as they meet tip-to-tip.

Reset actions, by contrast, SLAM components together violently to quickly bring all the chronograph hands back to zero. Reset hammers and cams are almost universally made of steel to survive the tremendous forces involved. In fact, in super slow motion, you’re likely to see the chronograph wiggle violently back and forth as it resets—but only at hundreds of frames per second.

If a chronograph was reset while its delicate clutch components were still meshed, the violent reset action would simply shear off all of those fine, delicate teeth on the clutch mechanism. So, a flyback mechanism has safeguards to make sure that the reset can be performed safely without any damage.

As you push the reset button, the reset hammer is tripped and quickly flies in toward the chronograph wheels. Just beforethe hammer hit the wheels, though, the reset hammer lifts the clutch lever out of the way, so power is removed from the system and everything can reset safely.

Once reset, a spring pulls the reset hammer back to its start point. As it “flies back,” the clutch is lowered back into engagement (if it was previously running) and the chronograph is allowed to keep going.

Want to add a flyback chronograph to your collection? Click here to shop the Atwood!